- Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom

-

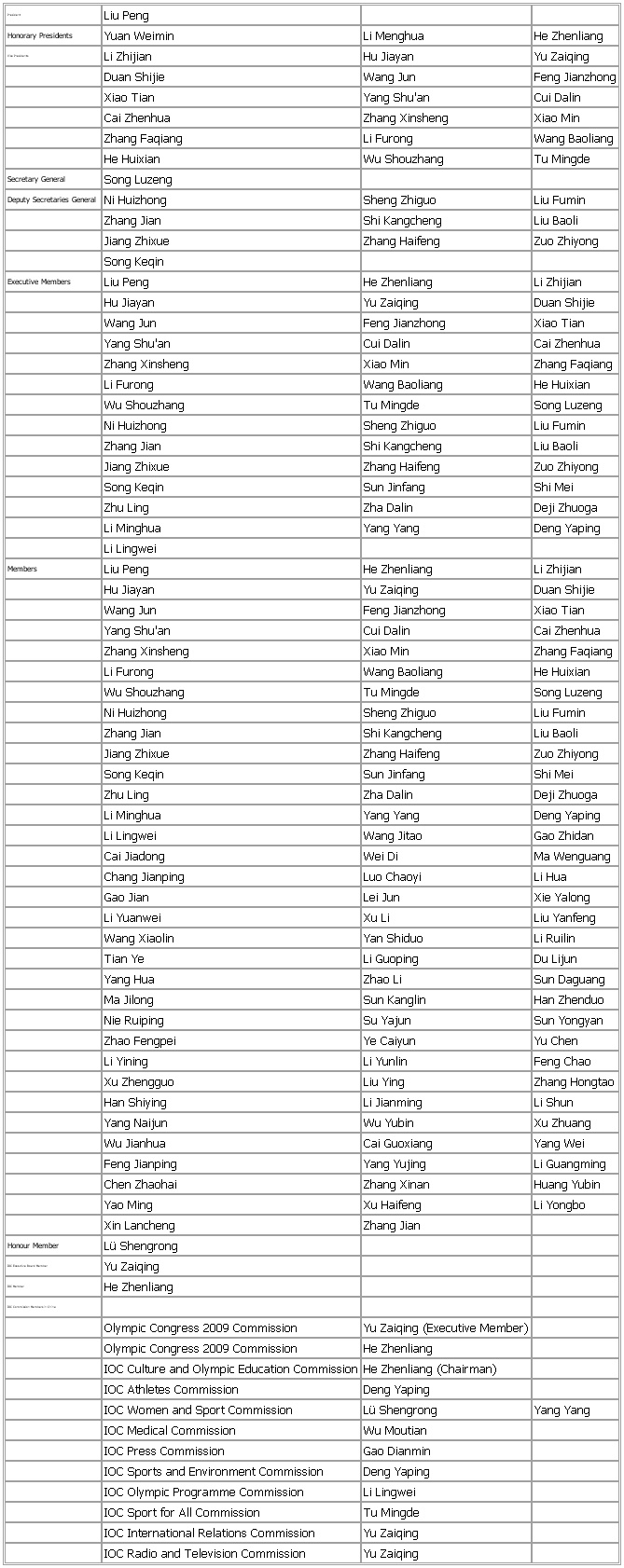

IntroductionThe Games of the XXIX Olympiad, involving some 200 Olympic committees and as many as 13,000 accredited athletes competing in 28 different sports, were auspiciously scheduled to begin at 8:08 PM on the eighth day of the eighth month of 2008 in Beijing, capital of the world's most populous country. From the time the International Olympic Committee selected Beijing as host city, on July 13, 2001, China invested huge sums of money in urban renewal, expanded infrastructure, and construction of Olympic facilities in Beijing and the six other Olympic venues ( Qingdao, Hong Kong, Tianjin, Shanghai, Shenyang, and Qinhuangdao). In the months prior to August 8, a devastating earthquake in Sichuan province, international focus on China's pollution problems, protests over China's human rights record and Tibet, and criticism of the Chinese government's control of information became part of the Olympics story. Nevertheless, China was determined to show the world, also through an Olympics lens, that it had joined the ranks of the world's most modern and influential countries.Britannica is pleased to showcase a broad selection of information on China and the Olympics, including a brief history (Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom) of China's association with the Olympics and a special essay (Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom) by Olympics expert Xu Guoqi; key facts (Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom) and articles about China, Beijing, and the six other Olympic cities; a calendar of key dates (Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom) in 2008; an essay (Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom) on China's explosive growth by researcher Dorothy-Grace Guerrero; the story of the Olympics (Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom) and Paralympics (Beijing 2008 Olympic Games: Mount Olympus Meets the Middle Kingdom), with tables of IOC presidents and 2004 medal winners; a colourful photo gallery; and a list of Web sites for additional information.2008 Olympic Updates: Key Events from Beijing● August 9: The first gold medal of the games went to Czech markswoman Katerina Emmons, who won the women's 10-metre air rifle event.● August 10: Guo Jingjing, two-time gold medal winner at the Athens Olympic Games, took home the third gold of her career as a member of the victorious Chinese team in the 3-metre synchronized springboard diving event.● August 11:● India's Abhinav Bindra won the first individual gold medal in his country's history by taking the men's 10-metre air rifle event.● American swimmer Michael Phelps (Phelps, Michael)—who won the 400-metre individual medley event on August 10—continued his historic quest for eight gold medals in one Olympic Games as a member of the winning American 4 × 100-metre freestyle relay team.● August 12:● Togo's Benjamin Boukpeti placed third in the men's single kayak slalom event. His bronze medal is the first Olympic medal in Togo's history.● China took home the gold medal in the men's team gymnastics event, the country's seventh win in the last eight Olympic and world championships combined.● American swimmer Natalie Coughlin repeated as gold medalist in the women's 100-metre backstroke event, defeating world record holder Kirsty Coventry of Zimbabwe in the final.● The first two wrestling gold medals of the Beijing Games were awarded to Russia's Nazyr Mankiev and Islam-Beka Albiev for winning the Greco-Roman 55-kg and 60-kg weight classes, respectively.● August 13:● American swimmer Michael Phelps (Phelps, Michael) won his 10th and 11th career Olympic gold medals—his fourth and fifth of the 2008 Games—to break the previous record of nine gold medals shared by Paavo Nurmi (Nurmi, Paavo), Larisa Latynina (Latynina, Larisa Semyonovna), Mark Spitz (Spitz, Mark), and Carl Lewis (Lewis, Carl).● China's women's gymnastics team won the country's first gold medal in the artistic team event.● The cycling individual time trial gold medals were won by Fabian Cancellara of Italy and Kristin Armstrong of the United States.● Chinese weightlifter Liu Chunhong defended her 2004 Athens Games gold medal by winning the women's 69-kg division of the weightlifting event. Liu broke world records in all three weightlifting categories—the snatch, the clean and jerk, and total weight.● August 14:● Tuvshinbayar Naidan of Mongolia won the first gold medal in his country's 40-year Olympic history by taking the men's 100-kg judo event.● Two-time world champion Yang Wei of China won the men's individual all-around gymnastics gold medal.● Japanese swimmer Kitajima Kosuke won the men's 200-metre breaststroke gold medal, his second gold of the 2008 Games and fourth overall.● The Ukrainian women's sabre team upset the top-seeded U.S. team and host China en route to winning the gold medal.● August 15:● Michael Phelps (Phelps, Michael) won his sixth Olympic event as he captured the gold in the 200-metre individual medley, breaking his own world record in the process.● American gymnast Nastia Liukin won the gold in the women's individual all-around competition. Teammate Shawn Johnson placed second, marking the first time that American gymnasts had finished in the top two positions in the women's all-around.● Brothers Pavol Hochschorner and Peter Hochschorner of Slovakia won their third consecutive Olympic gold medal in the men's double canoeing slalom event. The two had previously won the event in the Sydney Games in 2000 and in the Athens Games in 2004.● August 16:● Jamaica's Usain Bolt broke his own world record in the men's 100-metre sprint final by finishing the race in 9.69 seconds to earn his first Olympic gold medal.● Michael Phelps of the United States won his seventh gold medal of the Beijing Games in the 100-metre butterfly event to tie Mark Spitz (Spitz, Mark)'s Olympic record. Phelps won the race by 0.01 second.● August 17:● American swimmer Michael Phelps (Phelps, Michael) broke the 36-year-old record of gold medals won in a single Olympic Games—previously held by Mark Spitz—by winning his eighth gold of the Beijing Games as a member of the American 4 × 100-metre medley relay team.● Jamaica continued its domination of the sprints as all three medalists in the women's 100-metre sprint final—led by gold medal winner Shelly-Ann Fraser—hailed from that country.● China won the women's team table tennis event to break the country's record for gold medals in one Olympic Games with 33.● Rafael Nadal (Nadal, Rafael) of Spain won the gold medal in the men's tennis singles event, becoming the first player with a top-five ranking by the Association of Tennis Professionals to do so.● Russia's Elena Dementieva defeated countrywoman Dinara Safina to capture the gold medal in the women's tennis singles event.● August 18:● Russia's Yelena Isinbayeva broke her own women's pole vault world record by clearing 16 feet 63/4 inches (5.05 metres) and took her second consecutive Olympic gold medal in the event, repeating her victory in the women's pole vault at the 2004 Athens Games.● American Stephanie Brown Trafton captured the gold in the women's discus throw event.● Emma Snowsill of Australia won the gold in the women's triathlon.● August 19:● Cyclist Chris Hoy of Great Britain won the men's sprint, his third gold medal of the Beijing Games after wins in the men's keirin and team sprint events. Hoy is the first Briton in 100 years to take home three golds in one Olympic Games.● Russia's Mavlet Batirov won the men's 60-kg freestyle wrestling gold medal, four years after capturing the 55-kg gold at the 2004 Athens Games.● Li Xiaopeng of China won the men's parallel bars gymnastics event. Previously, Li took the parallel bars gold at the 2000 Sydney Games and won a bronze medal in the event at the Athens Games.● August 20:● Usain Bolt of Jamaica won his second sprinting gold medal of the Beijing Games by taking the 200-metre sprint in 19.30 seconds, breaking Michael Johnson (Johnson, Michael)'s 12-year-old world record in the process.● Bouvaisa Saitiev of Russia won his record-tying third career wrestling gold medal by taking the men's 55-kg freestyle event. Saitiev also won wrestling golds at the 1996 and 2004 Games.● Russia's Larisa Ilchenko won the gold in the women's 10-km marathon swim. South Africa's Natalie du Toit, the first female amputee to compete in an Olympics event, finished 16th.● August 21:● The Japanese softball team upset the favoured U.S. team to take the softball final. It was the United States' first Olympic softball loss in eight years.● The American women's soccer team scored a goal in extra time to win the gold medal match over Brazil, 1–0.● Americans Misty May-Treanor and Kerri Walsh won the women's beach volleyball gold medal, duplicating their victory at the 2004 Athens Games.● Jamaica's Veronica Campbell-Brown won the women's 200-metre sprint, giving her country a sweep of the men's and women's sprint events at the Beijing Games.● Danielle de Bruijn scored seven goals—including the game winner, with 26 seconds left—in The Netherlands' upset victory over the top-seeded U.S. team in the women's water polo final.● August 22:● American Bryan Clay won the men's decathlon gold medal four years after finishing with the silver at the Athens Games in 2004.● France's Anne-Caroline Chausson and Latvia's Maris Strombergs won the women's and men's inaugural Olympic BMX cycling gold medals. BMX racing was added to the Olympic schedule for the first time at the Beijing Games.● Philip Dalhausser and Todd Rogers of the United States took the men's beach volleyball gold medal, making the United States the first country to sweep both Olympic beach volleyball golds since the discipline debuted in 1996.● The women's and men's 4 × 100 sprint relays were won by the Russian and Jamaican teams, respectively.● August 23:● American runners swept both the men's and women's 4 × 400 relay races, with the men's team winning their race in Olympic record time.● South Korea defeated Cuba 3–2 to win the baseball gold medal.● The U.S. women's basketball team won its fourth consecutive Olympic gold medal, beating Australia 92–65.● Brazil took the gold in women's volleyball, defeating the United States for the country's first Olympic win in the event.● August 24:● The U.S. men's basketball team—featuring such National Basketball Association superstars as LeBron James, Kobe Bryant (Bryant, Kobe), and Carmelo Anthony (Anthony, Carmelo)—defeated Spain 118–107 for the gold medal in the event.● Kenya's Sammy Wanjiru won the men's marathon, the first Olympic gold in the event in the country's history.● The American men's volleyball team won its first gold medal in 20 years, beating top-seeded Brazil in the event final.● Zou Shiming won the light flyweight (48-kg) boxing gold medal, the first boxing gold in China's history.● At the close of the Beijing Games, China had won the most gold medals (51), and the United States had the highest total of medals (110).2008 Olympic Games Final Medal RankingsChina and the Olympics (Olympic Games)China's Participation in the Olympic GamesThe First Games and the First AthletesChina's association with the Olympic movement progressed slowly in the early years. The first Chinese member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Wang Zhengting, was elected in 1922 at the 21st IOC Session Meeting in Paris. It was not until 1932, however, that China actually sent a delegation to the Olympics, the Games of the X Olympiad, held in Los Angeles. Three months before those Games, Chinese newspapers suddenly reported that the puppet state of Manchukuo (Manchuguo), created by the Japanese in China's Northeast (Manchuria), was planning to send two athletes. People throughout China expressed their anger and resentment over this. Under fire from the public, China's Nationalist government quickly decided to send a delegation, which included only one athlete, runner Liu Changchun, to the Games. Although Liu failed to qualify in the 100-metre event after his long ocean journey, he became the first Chinese athlete to compete in the Olympic Games, and thus the 1932 Los Angeles Games became the first Olympics for China.The First MedalsAfter the Chinese communists took control of mainland China, establishing the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, and the Nationalist government (Republic of China, ROC) fled to Taiwan, the question of which side should represent China at the Olympic Games became a big political issue. From the PRC's point of view, two Olympic Committees representing one nation violated the Olympic Charter, and thus it refused to participate in the Games for some two decades. During that time, the ROC maintained its position on the IOC, and athletes from Taiwan participated under the name of China in several Games in different countries. Yang Ch'uan-kuang (Pinyin: Yang Chuanguang), an athlete from Taiwan, won a silver medal in the men's decathlon at the 1960 Rome Games, the first medal ever won by a Chinese participant in the Olympics. In 1968 Chi Cheng (Pinyin: Ji Zheng), also from Taiwan, won a bronze medal in the women's 80-metre hurdles in the Mexico City Games, becoming the first female Chinese athlete to win an Olympic medal.The First Gold MedalsIn October 1979 the Executive Committee of the IOC reinstated the PRC's membership on that committee, while Taiwan was allowed to compete under the name Chinese Taipei. Because the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan led many countries to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics, the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics became the first Summer Games to which the PRC sent a delegation. The delegation consisted of 353 members, with 224 athletes participating in 16 events. Sharpshooter Xu Haifeng won a gold medal in the men's 50-metre pistol event and became the first Chinese in Olympic history to win the highest honour. In addition, Wu Xiaoxuan won a gold medal in the women's 50-metre rifle three-positions shooting competition, becoming the first Chinese woman to win a gold medal. Their success was called “breaking through zero” in China. Altogether, the Chinese athletes won 15 gold, 8 silver, and 9 bronze medals at those Games, ranking fourth overall in the gold medal tally. Athletes from Taiwan also won 2 bronzes.Bid to Be Host CityHaving successfully hosted the 11th Asia Games in 1990, the city of Beijing felt encouraged to bid for the right to host the Olympic Games. Early in 1991 the city government of Beijing and the National Olympic Committee of China decided to bid for the XXVII Olympic Games in 2000. Beijing was selected by the IOC as one of the candidate cities, along with Sydney, Berlin, Brasilia, Istanbul, and Manchester, Eng. At the 101st session of the IOC, held in Monte Carlo in 1993, the representatives of the candidate cities made their final presentations, and the 88 IOC members voted on the selection. Although a number of Western countries, citing human rights issues, refused to vote for Beijing, it was one of two cities left after the third round of voting. In the last round, Beijing lost to Sydney by the narrow margin of two votes.In 1999 China launched its second bid. On September 6 the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games Bid Committee was established, and in mid-2000, Beijing submitted its bid to the IOC. Included in it were answers to 22 questions from the IOC questionnaire as well as the plan and conceptual goals for the Games, which were to take as their motto “New Beijing, Great Olympics” and focus on being a “green” Olympics, a “hi-tech” Olympics, and the “people's” Olympics. Of the 10 cities bidding for the 2008 Games, the IOC in August 2000 selected five candidates: Beijing, Toronto, Paris, Istanbul, and Ōsaka, Japan.On January 13, 2001, the Beijing Olympic Games Bid Committee officially submitted its bid to the IOC. The three-volume report contained 18 themes, some of which were national, regional, and candidate-city characteristics; customs and immigration formalities; environmental protection and meteorology; finances; marketing; provisions for the Paralympic Games; plans for the Olympic Village; medical/health services; security; accommodations; transport; and guarantees. Support letters from national and city government leaders were also included. One month later an IOC evaluation team visited Beijing to determine the city's capacity to host the Games. In an appraisal by the Evaluation Commission on May 15, 2001, Beijing's bid was rated “excellent,” the city receiving the support of 94.9 percent of its residents to host the Games. The report concluded that a Beijing Olympics would “leave a unique legacy to China and to sports.”At the 112th session of the IOC in Moscow, on July 13, 2001, the final decision was made. All five candidate cities made a 45-minute presentation and took 15 minutes of questions from committee members. Beijing was the fourth to give its presentation. After speeches by Vice Premier Li Lanqing and other representatives of the Beijing Olympic Games Bid Committee, Chinese IOC member He Zhengliang said:Mr. President, dear colleagues, no matter what decision you make today, it will be recorded in history. However, one decision will certainly serve to make history. In your decision here today, you can move the world and China toward an embrace of friendship through sports that will benefit all mankind. By voting for Beijing, you will bring the Games—for the first time in the history of the Olympics—to a country with one-fifth of the world's population and give to this billion people the opportunity to serve the Olympic Movement with creativity and devotion. If you honor Beijing with the right to host the 2008 Olympic Games, I can assure you, my dear colleagues, in seven years Beijing will make you proud of the decision you make here today.After the presentation, the IOC started to vote. In the first round, Beijing received 44 votes, Toronto 20, Istanbul 17, Paris 15, and Ōsaka 6. In the second round, Beijing had 56 votes, more than half of the total, Toronto 22, Paris 18, and Istanbul 9, with Ōsaka eliminated due to the results of the first round. Thus Beijing was honoured to be awarded the 2008 Olympic Games, the first time in Olympic history that a city in the world's most populous country would host the world's most important sporting event.China's Olympic Dream FulfilledWith the staging of the Olympic Games in Beijing in August 2008, China's century-long dream became a reality, the culmination of collective efforts of several generations of the Chinese people.Chinese interest in the Olympics coincided with a search for a new national identity and a move toward internationalization, which began by the turn of the 20th century—when the modern Olympic movement started. Following the first Sino-Japanese war in 1895, many Chinese felt that their country had become a "sick man" who needed strong medicine. The Olympic Games and modern sports in general became such medicine. The Chinese began to associate physical training and the health of the public with the fate of the nation. Ideas such as social Darwinism and survival of the fittest, which were introduced at this point in time, prepared the Chinese mentally for their embrace of Western sports. This idea of using sports to save the nation—and later to showcase China's greatness—became a widespread notion among many Chinese. Not surprisingly, Mao Zedong's first known published article was about physical culture, and, when in 2001 the IOC awarded the 2008 Olympics to Beijing, the leaders of China launched an all-out effort to make their Olympic Games a success.To a great extent, China's involvement in the modern Olympic movement reflects its determination to use sports to join the world as an equal and respected member. The China National Amateur Athletic Federation was established in 1921 and was subsequently recognized by the IOC as the Chinese Olympic Committee. In 1922, when Wang Zhengting became the first Chinese member of the IOC (and the second member from Asia), his election symbolized the beginning of China's official link with the Olympic movement.China's first participation in the Olympic Games came about largely for diplomatic reasons, when Japan tried to legitimatize its control of Manchukuo with a plan to send a team to the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics to represent that puppet state. China responded by sending sprinter Liu Changchun, who was called in the official 1932 Olympic Games report "a sole representative of 400 million Chinese." Chinese athletes under the Nationalist regime took part in both the 1936 and the 1948 Olympics despite a long war with Japan and later with the communists.In 1949 the Communist Party defeated the Nationalist government and forced the Nationalist retreat to Taiwan. From the 1950s until the late 1970s, both Beijing and Taipei claimed to represent China and did everything possible to block the other from membership in the Olympic family. Heated disputes surrounding their exclusive membership claims plagued the international Olympic movement for many years. In 1958, to protest Taiwan's membership in the Olympic family, Beijing withdrew from the Olympic movement, and it did not return until 1979.The 1980 Summer Olympic Games would have been an excellent moment for Beijing to showcase the arrival of a new and open China after its return to the Olympic movement. Unfortunately, the Olympic Games that year were held in Moscow, and the Chinese government decided to follow the U.S. boycott of the Games. Beijing had to wait another four years until the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. However, there seemed to be no better place and timing for Beijing than the 1984 Games. After all, it was in Los Angeles 52 years earlier that China had taken part in the Olympic Games for the first time, and, because of the Soviet Union's boycott of the Los Angeles Games, China had a chance to claim more medals, garner special treatment from the American fans, and even play a saviour's role for that year's Olympics. It was a glorious moment for China. Chinese athletes had never before won an Olympic gold medal, but in 1984 they earned 15. In 1932 China had sent only one athlete to take part in its first Olympic Games, but 52 years later, in the same city, 353 Chinese athletes competed for their country. During the 1984 Los Angeles Games, China officially informed the world that it wanted to host the Olympics.The 1984 Olympic Games were just a beginning, as China's growing success as a world-class economic power was paralleled in the realm of sports. At the 2004 Athens Olympics, China competed with the United States for medal supremacy: the U.S. took 36 gold medals, while China finished a close second with 32. The 2008 Beijing Games were seen as an excellent opportunity for the Chinese to show the world a new China—open, prosperous, and internationalized—and to help the Chinese demonstrate their can-do spirit and cure their past strong sense of inferiority and thus become confident in themselves and their nation. The Olympic Games bring along many challenges to their host and to the rest of the world, but, no matter what results, the 2008 Games in Beijing will be remembered as a major turning point in China's search for national identity and its relations with the world community.Xu GuoqiChina's Olympic Organizing CommitteePresident Liu PengHonorary Presidents Yuan Weimin Li Menghua He ZhenliangVice Presidents Li Zhijian Hu Jiayan Yu ZaiqingDuan Shijie Wang Jun Feng JianzhongXiao Tian Yang Shu'an Cui DalinCai Zhenhua Zhang Xinsheng Xiao MinZhang Faqiang Li Furong Wang BaoliangHe Huixian Wu Shouzhang Tu MingdeSecretary General Song LuzengDeputy Secretaries General Ni Huizhong Sheng Zhiguo Liu FuminZhang Jian Shi Kangcheng Liu BaoliJiang Zhixue Zhang Haifeng Zuo ZhiyongSong KeqinExecutive Members Liu Peng He Zhenliang Li ZhijianHu Jiayan Yu Zaiqing Duan ShijieWang Jun Feng Jianzhong Xiao TianYang Shu'an Cui Dalin Cai ZhenhuaZhang Xinsheng Xiao Min Zhang FaqiangLi Furong Wang Baoliang He HuixianWu Shouzhang Tu Mingde Song LuzengNi Huizhong Sheng Zhiguo Liu FuminZhang Jian Shi Kangcheng Liu BaoliJiang Zhixue Zhang Haifeng Zuo ZhiyongSong Keqin Sun Jinfang Shi MeiZhu Ling Zha Dalin Deji ZhuogaLi Minghua Yang Yang Deng YapingLi LingweiMembers Liu Peng He Zhenliang Li ZhijianHu Jiayan Yu Zaiqing Duan ShijieWang Jun Feng Jianzhong Xiao TianYang Shu'an Cui Dalin Cai ZhenhuaZhang Xinsheng Xiao Min Zhang FaqiangLi Furong Wang Baoliang He HuixianWu Shouzhang Tu Mingde Song LuzengNi Huizhong Sheng Zhiguo Liu FuminZhang Jian Shi Kangcheng Liu BaoliJiang Zhixue Zhang Haifeng Zuo ZhiyongSong Keqin Sun Jinfang Shi MeiZhu Ling Zha Dalin Deji ZhuogaLi Minghua Yang Yang Deng YapingLi Lingwei Wang Jitao Gao ZhidanCai Jiadong Wei Di Ma WenguangChang Jianping Luo Chaoyi Li HuaGao Jian Lei Jun Xie YalongLi Yuanwei Xu Li Liu YanfengWang Xiaolin Yan Shiduo Li RuilinTian Ye Li Guoping Du LijunYang Hua Zhao Li Sun DaguangMa Jilong Sun Kanglin Han ZhenduoNie Ruiping Su Yajun Sun YongyanZhao Fengpei Ye Caiyun Yu ChenLi Yining Li Yunlin Feng ChaoXu Zhengguo Liu Ying Zhang HongtaoHan Shiying Li Jianming Li ShunYang Naijun Wu Yubin Xu ZhuangWu Jianhua Cai Guoxiang Yang WeiFeng Jianping Yang Yujing Li GuangmingChen Zhaohai Zhang Xinan Huang YubinYao Ming Xu Haifeng Li YongboXin Lancheng Zhang JianHonour Member Lü ShengrongIOC Executive Board Member Yu ZaiqingIOC Member He ZhenliangIOC Commission Members in ChinaOlympic Congress 2009 Commission Yu Zaiqing (Executive Member)Olympic Congress 2009 Commission He ZhenliangIOC Culture and Olympic Education Commission He Zhenliang (Chairman)IOC Athletes Commission Deng YapingIOC Women and Sport Commission Lü Shengrong Yang YangIOC Medical Commission Wu MoutianIOC Press Commission Gao DianminIOC Sports and Environment Commission Deng YapingIOC Olympic Programme Commission Li LingweiIOC Sport for All Commission Tu MingdeIOC International Relations Commission Yu ZaiqingIOC Radio and Television Commission Yu ZaiqingSee as table: